**Guest blogger Randy Christian is a crew member on R/V Sally Ride, but this month is working on FLIP, Scripps’ FLoating Instrument Platform. FLIP is deployed on a project offshore of Southern California, accompanied by other members of the SIO fleet, R/V Sproul and R/V Sally Ride. You can learn more about Randy in this blog post introducing him as second mate, though he sometimes sails as third mate. Learn more about FLIP’s history and specs, including video of it flipping, here. **

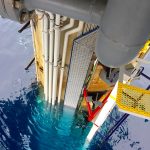

Flip, as photographed from one of the boom arms, will be home for the next

few weeks. Photo by Randy Christian.

Research Platform Flip is one of a kind. She was designed and built as a four-year Navy project on a budget of roughly $500,000, according to the vessel’s Captain/Chief Engineer of 30 years (and my boss of the past four days), Tom Golfinos. This was during the Cold War, with the advent of nuclear submarines, and the U.S. Navy was suddenly very interested in learning more about the ocean. The vessel was designed to be towed in the horizontal position, and, when on location in deep water, to have ballast tanks in the cylindrical aft portion of the vessel flooded with a series of valves much like a submarine. Flip is a ship that goes vertical. This vertical position then gives the platform numerous advantages over your average oceanographic research ship. With a 300 ft draft, she is incredibly stable, and with no engines turning propellers (only a single generator for power), she is exceedingly quiet. All of this adds up to a platform perfectly suited to studying numerous aspects of the ocean, from subsurface currents to sound wave propagation; important stuff to know about if you’re navigating the depths and trying to find Soviet submarines before they find you. Needless to say, that four-year project “got extended one year, and then fifty more,” as Tom says in his thick Greek accent. Flip turns 55 this June, and much of what we know about the physical properties of the ocean can be traced back to her. Now operated by UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO), R/P Flip is still owned by the U.S. Navy’s Office of Naval Research (ONR).

I am on loan to the Flip from my usual gig as Third Mate aboard the brand new R/V Sally Ride (also owned by ONR and operated by SIO), and this is an exciting opportunity. There aren’t many professional mariners who have flipped a ship 90° and lived to tell the tale, much less who’ve done so on purpose and considered it a resume builder. In the horizontal position, Flip’s layout is odd. Rooms are narrow and tall, there are sideways doors, hatches, catwalks, and ladders, like an Escher drawing come to life. There is even a sideways shower and sink, occupying the same room as a right-side-up (for now) sink and toilet. Reefers and freezers, the entire galley, deck lockers, and all of the bunks are all on gimbals, so they can rotate freely when it comes time to flip the Flip.

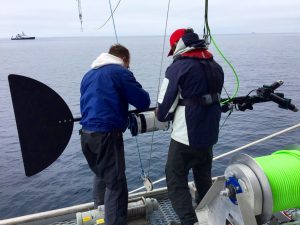

Chief Scientist Laurent (left) and researcher Nick prep an ADCP for deployment.

R/V Sally Ride operates in the background. Photo by Randy Christian.

According to the Chief Scientist for this trip, Laurent Grare, a wiry Frenchman with a near-constant smile who is one of the hardest workers I’ve ever seen, Flip is ideally suited to study the interface between the air and the ocean. As wind blows over the water, it stirs up cylindrical currents with an axis parallel to the direction of the wind. Laurent and his team will be deploying and testing acoustic profilers, infrared cameras, and various other sensors with the goal of better understanding how this process works.

With five crew (myself included) and nine scientists aboard, we depart Scripps’ Nimitz Marine Facility in Point Loma at 13:00 on the 15th of March, and are towed out of San Diego Bay by the tug J.M. Hidalgo. I have the 20:00-24:00 watch, which, since we’re under tow, is much easier than what I’m used to. We are towed through the night around the northern end of San Clemente Island to a point about equidistant from San Clemente, San Nicholas, and Santa Barbara Islands, and at around 05:00 on the morning of the 16th, the fun begins. After disconnecting from the tug, we get to work on final preparations. These include tying our personal gear down to our racks, checking that all gear is stowed securely in the lower aft corner of every space so that nothing will drift when turned 90°, ensuring all pins are pulled and all gimbals are rotating freely.

Everyone has an assigned station for the flip, and mine is on the bow with experienced crewmember, Johnny Rodrigues. All hands don life jackets as Johnny and I work our way forward to the bow, closing heavy grating doors behind us, which will become decks. After Tom starts opening valves, the flipping process takes about 25 minutes total. There is not much noticeable change in the first 10-15 minutes, but then the decks start getting a bit slanty, and as the process proceeds it occurs to me that I hope this is the only situation in which I will ever have this feeling. Once we get to about 30°, things start to accelerate and get exciting in a hurry. The sound of water rushing up the sinking hull is audible from the bow, and I hear Tom shouting, “Get ready! Get ready!”

Everyone is bracing himself or herself in some sort of position, ready to either step from deck to bulkhead, or lying against the bulkheads, which will shortly transform into decks. I am holding onto the capstan, facing aft and spotting my landing on the bulkhead in front of me. Suddenly there is a rush of acceleration as Flip slings itself upright, and I step gingerly onto my landing spot. For a moment it almost feels as though she’s going to keep going right over, but instead she starts spinning, like someone put the rudder hard over. After a couple of rotations, she settles out, and the flipping process is done. Flip is now a tree house floating in the middle of the ocean.

Now the work begins, and there is much to do. Setting three anchors with 640 ft. of chain, 60 ft. of cable, and over 6,000 ft. of thick synthetic hawser each with the help of the tug J.M. Hidalgo and the R/V Robert Gordon Sproul (another SIO vessel) will take several hours, and once that is completed, Flip will not move for 26 days. All spaces are checked to make sure everything gimbaled rotated as intended. Finding my way around is a bit tricky and disorienting at first, as the entire deck plan has transformed. Every room on Flip suddenly has much more deck space in the vertical position, and as the scientists begin to break out their gear, set up tables, and run wires, it becomes clear that one of the most stunning transformations will be the lab.

Meanwhile, out on deck, The Old Man, Johnny Rod, Dave Brenha, and I are climbing, rigging, heaving, and hauling. There are three 60-foot-long booms to deploy, a 40- foot radar tower to erect, and several heavy winches and air-tuggers to move and bolt into position, and Flip’s only motorized lifting device is the capstan on the bow I used to steady myself during the flip. This means a great deal of rigging, using pad-eyes, shackles, lifting straps, and snatch-blocks to create fair leads through which lines can be run up to the capstan. This setup will take us the next three days, and they are long, physical days of intense labor. We all clock over 25 hours of overtime each in these first three days, but it is gratifying work, and we can see the results. Matrik, the cook, has ravenous mouths to feed.

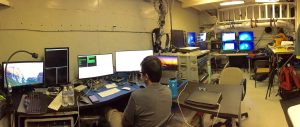

As we get the booms deployed, the scientists are affixing their array of sensors to them and running wires back to the lab, which before long looks like a high-tech command center, with 15 flat screens all streaming data, or about to. We assist with the deployment of a few instruments that will remain submerged, collecting data for our entire time out here.

Lab space aboard FLIP, set up after the platform is vertical. Note the ladder on the wall/ceiling.

Photo by Randy Christian.

By the time Sunday rolls around, things start to mellow out, and I am grateful be able to get some rest. “Now it’s just doing time,” Dave says casually and with a wry grin. While this may be old hat for him and Johnny, for me it’s new and different from anything I’ve ever done before, and has more the feeling of summer camp than prison. There are bright, intelligent people to talk to about fascinating things, there is science to facilitate, and there is meat on the grill. Morale is high, and, barring any unforeseen disasters, I get the sense it will stay that way. The close quarters and the nature of the work leave no room for complainers, victims, or layabouts. Everyone aboard is friendly and positive, enthusiastic about their work and the ocean, multi-skilled, hard working, and problem solving by nature. I have heard the phrase “teamwork makes the dream work” uttered more than once since we flipped and got to work. As corny as the phrase is, it is appropriate. We are all working together for the acquisition of data that will be used in the project of science, the careful and systematic study of our ocean and our planet, and the broadening of our understanding of how it all works. It is a worthy dream indeed.

- Being towed out of San Diego Bay. Note the booms stored back and walkway along the length. Photo by computer tech Daniel Yang.

- Lab before flipping. Note the ladder and compare its orientation to lab photo above. Photo by Randy Christian.

- Galley. Everything from the stove to the shelves are on tracks for flipping. Photo by Randy Christian.

- Flipping the toilet. Note the two sinks, one in each orientation, and the floor of the shower on the “wall.” Photo by Randy Christian.

- After flipping. Note the orientation of the metal walkway. Photo by Randy Christian.

- Galley. Everything from the stove to the shelves are on tracks for flipping. Photo by Randy Christian.