The first science verification cruises (SVCs) scheduled on the R/V Sally Ride are fast approaching. September will be the month to test out various winches, wires, and pretty much every other system in the lab spaces onboard to make sure everything’s ready for the ship to enter full service at SIO. Dr. Bill Hodgkiss will be the chief scientist for the first SVC, which means he will make up the science plan and work with the captain and restech (marine research technician) to execute that plan in a safe and effective manner. We just had the pre-cruise meeting, which takes place at least a month in advance of every cruise on any of the ships in the SIO fleet. We went over the specific plan, which equipment will be used, how many people will be needed to operate it, what the expectations of the crew will be, and any other ideas that needed to be discussed. Present at this meeting were two restechs, the port captain and engineer, chief scientist and a few people from his lab, as well as the ship’s captain and chief engineer (via phone from Anacortes). I was there as well, as I will be sailing on the cruise to document it for posterity, and hopefully can be of some use as a technician as well.

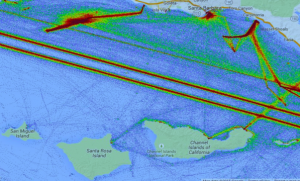

Sally Ride’s first SVC will take place in the Santa Barbara Channel, the waterway between the Northern Channel Islands and mainland California. It will take us about 24 hours to get there from San Diego. This area is a popular shipping lane; the nearby Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach combined are the 9th busiest cargo port in the world. Ship traffic in busy areas is regulated just like street traffic when you’re driving. As you can see in the below figure showing the density of ship traffic, it is organized into well-used traffic lanes, just like we’re used to on freeways. The blue area in between the southbound and northbound traffic is called the separation zone and acts as a barrier, like the freeway median. The R/V Sally Ride will loiter in that area and carry out basic seawater measurements (conductivity, temperature, depth) in the water column, while the deployed instruments collect data.

Every registered ship in the world has a unique tracking identifier, called automatic identification system (AIS), that relays the ship name, location, course (direction of travel), and speed to nearby ships. There is a screen on the bridge that shows these – on ocean crossings, it’s a big event when one pops up. I know I’ve gotten excited to see a ship on the radar and through the porthole after weeks of no other signs of human life outside ourselves. In those circumstances it’s often a car or other cargo carrier headed between two busy ports. In this instance the AIS map will likely be crowded, with dozens of ships within the screen’s ~20 mile radius. The AIS data will be matched up later to the noises recorded by the deployed instruments.

Dr. Hodgkiss is a professor at Scripps, as well as at the Jacob’s School of Engineering on the main UCSD campus. His lab group at the Marine Physical Laboratory (MPL) designs acoustic devices that can be deployed below the surface of the ocean.

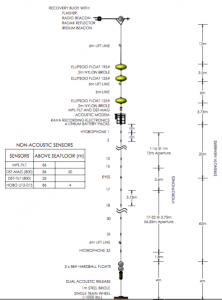

Anchored by a 1,000-pound train wheel, a string of acoustic equipment will be lowered to the ocean floor. The depth in this area is in the 500-580 meter range, and each array is assembled to stay as close to the seafloor as possible to avoid too much side-to-side movement in the currents. A total of 32 hydrophones are connected in a line, collecting data at various depths and over a range of frequencies. Large floats are included near the top of the mooring string in order to keep the array as straight in the water column as possible. After a week in the ocean, the instruments will be recovered. A signal is sent from the ship, and the line detaches at the release point just above the anchor. The floats are enough the bring the entire string to the surface, and a flashing beacon activates, making it relatively easy for the ship to find.

The yellow ellipsoid floats that will be attached to the acoustic array,

with a technician for scale. Photo courtesy of the Hodgkiss lab.

Verification cruises like this one are a great opportunity to get important science done while also testing out the ship’s systems and operations – everything from the climate control in the labs to the winches used to lower equipment to the bottom of the ocean. There’s a lot to be done still before the ship is fully operational, but a successful first scientific verification cruise will be a big step in that direction. Wish us luck, and follow along in future posts!